| 1. On Technique, Craft and Style

I assume that you make pictures seriously because you wish to present an experience (visual and emotional) in clear visual form which will at once represent the picture’s subject and be in some way symbolic of human feelings. These feelings can be in relation to many things ranging from the subject itself to what Flannery O’Connor called this latter “the actual mystery of our position on this earth.”

I also assume that you wish your pictures to move people, and that to some of you this means not only people you know but people you don’t know and will most likely never meet.

All pictures that move people do so by the same means, whether the photographer be professional or amateur, known or anonymous, an artist or a worker in one of the many fields of professional photography. It is only the employment of these means that changes and varies with the photographer, his equipment, the predominate styles of his era, his own style, and his knowledge and employment of materials, technique and craft. As the important contemporary American photographer Jan Groover often told her students, “There are no rules.” There are only the way pictures work.

The employment of technique and craft, which are the foundations of personal style, depend on the photographer’s knowledge of how pictures work.

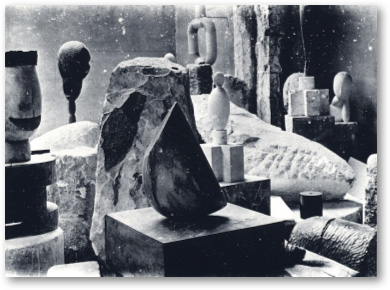

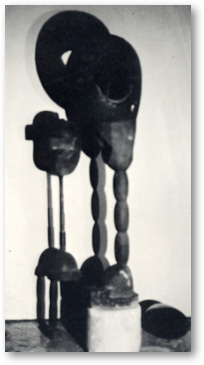

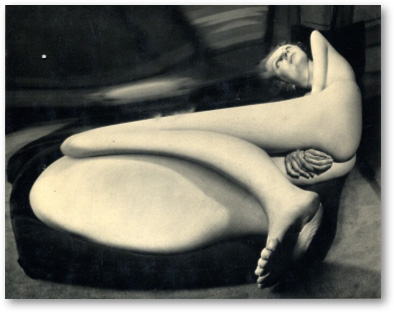

An event in the career of the important Rumanian modernist sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) who worked in Paris is relevant here.

When, in the 1920s, Brancusi became dissatisfied with professional, highly detailed, beautifully printed photographs of his sculptures reproduced in art journals he took a few photography lessons from the American photographer Man Ray (1890-1977), built a darkroom in his studio and began to photograph his sculptures. A few weeks later he showed Man Ray his first prints.

They were flat, fogged, stained, chipped and battered, with plaster dust and sawdust dried into the emulsion. But these, he told Man Ray, were the true pictures of his work. His further mastery of technique served only to improve the craft of his rough, primitive style.

|

|

Today these prints are the great ones.

Technique, craft, subject matter, materials, even working conditions are means, not ends in themselves.

|

Eric Lindbloom’s Diana camera pictures of Italian Renaissance sculpture, in his book Angels at the Arno (David R. Godine, publishers)

are as strong in their way as Clarence Kennedy’s view camera pictures of the same subject.

When Andre Kertesz, in his nineties, having long given up photographing in the streets, didn’t want to wait to see his pictures come back from the lab he made Polaroid SX-70 pictures of bric-a-brac on his window sill.

They are as visually sophisticated and strong, as charming and moving, as his great Leica pictures from the streets of Paris

and New York.

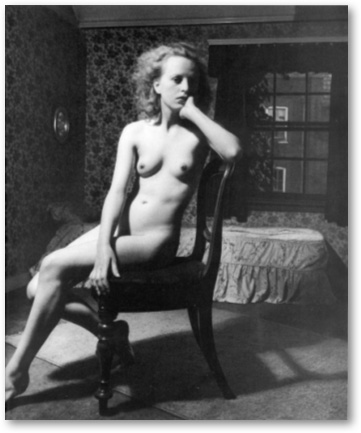

Of the twentieth-century’s three greatest bodies of black-and-white nudes, Edward Weston’s were made with an 8x10 view camera

|

Bill Brandt’s with a police department crime scene camera,

|

|

| And Kertesz’ on a 3x4-inch bellows camera with some lens movements.

Weston and Brandt photographed their models directly, Kertesz photographed the reflections of his models in fun house distorting mirrors.

|

|

The D-Day negatives by Robert Capa that survived the invasion fleet’s faulty darkroom procedure produced affecting pictures whose strength derives from a combination of Capa’s original composition, drawing, handling of space, etc. and the effects of the damage on them.

After World War II, many photographers, including W. Eugene Smith,

and Robert Frank

turned the grain, blur, shallow depth of field, rough tonal gradation and narrow latitude that were then considered as flaws of small camera photographs into powerful expressive means.

In digital photography, today’s “noise” is bound to be tomorrow’s expressive means (if it isn’t already yesterday’s).

2. The Defining Term is “Picture”

The alpha and omega of our efforts are pictures. “Picture” is the defining term.

Saying “picture” instead of either “image” or “photograph” is one of the most useful things you can do to improve your work. “Image” confuses the issue. Any image of something, inso far as it represents the thing, is as successful as any other.

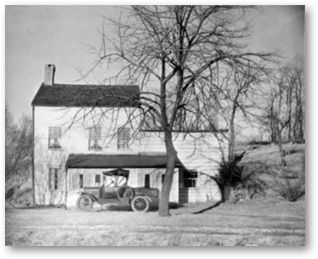

| Considered as an image, a child’s drawing of a house |

|

| a Walker Evans photograph of a house |

|

| and an Edward Hopper painting of a house |

|

are equally successful because we say “house” when we look at all of them.

As for “photograph,” it is accurate but limiting. Photography came into being in the 1830s but pictures have been in existence for thousands of years; and a photograph is only one kind of picture. Saying “photograph” narrows your field of reference to the accumulated discoveries of just under one hundred seventy years’ work within one branch of picture making. Also, in ordinary usage, “photograph” always implies a picture of something. Saying “photograph”, then, puts too much emphasis on the subject, to little on the form of the picture; thus it can mislead us into thinking that the strength and/or importance of the picture depends on the strength and/or importance of the subject when, in fact, they depend on the forms. As Garry Winogrand once said, “If a dramatic subject were the guarantee of a dramatic photograph, every picture of a close play at home plate would be a masterpiece.”

In the West, the first photographers’ reference point was the accumulated pictorial tradition of Western paintings, drawings and prints, from the Renaissance forward. The first word for photographs was “drawings” and “photograph” means “light drawing.” This is only to say that photographs are pictures; as photographers, our point of departure is in pictures. Like other pictures, photographs are the pursuit of beauty by specific means.

In the West, the first, and still one of the most useful investigations of pictures (useful to all picture makers) is the short, clear, plain-speaking treatise, On Painting, written in Florence, Italy, in 1435-6 by the Renaissance architect, painter, writer and humanist Leon Battista Alberti, whose excellence in so many fields, including mathematics and ancient Greek and Roman literature, gave rise to our term, “Renaissance man.”

One of the aims of picture making, Alberti says, is to “hold the eye and soul of the observer.” He says this prominently twice. Each time, “the eye” comes first.

Here are links to websites where you can study, in centuries’ worth of art, many of the ways painters and photographers have found to make their pictures hold the eye. The Web Gallery of Art, http://www.wga.hu/index1.html containing scans of painting, graphic works and sculpture from the late Gothic period to 1750. Mark Harden’s Artchive, www.artchive.com, which spans the early Renaissance to the present day and includes photography and non-Western art (click on the Mona Lisa icon and use the artists’ index in the left-most column). Masters of Photography, www.masters-of-photography.com containing good selections from a large number of historical and contemporary photographers.

In this column I will address myself to matters of how photographs hold the eye.

3. Beautiful Vernacular Photographs

The term (from criticism) may be unfamiliar but most of us have seen the objects it refers to, in thrift stores, at swap meets, garage sales and flea markets, or in a friend’s or a stranger’s family album: commonplace pictures in the commonplace amateur or professional photography style of a particular time or place. Most often we have no personal knowledge of, or connection to the person, place, thing or event the picture shows. Yet we feel something for the subject. Often this feeling lingers long afterwards. If we remember the picture years later, this same feeling sometimes comes back almost as strong. Yet we know nothing more about the subject than what the picture shows us. Often the subject or subjects are not themselves either beautiful or striking. So this feeling we get can’t come from the subject. Moreover, vernacular photographs are often by anonymous amateurs or anonymous journeymen, so the feeling can’t be something evoked by the maker’s name. Therefore, it must come from the picture itself.

My friend the photographer Paola Ferrario, who was just awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in photography, recently told me about an anonymous vernacular photograph she bought in a second hand store in Ireland a few years ago. As she gave it to a friend, all I can talk about is Paola’s description.

“It was,” she writes, “a print from the nineteen fifties from an under exposed negative. It was flat to the point that there were no blacks. The tones were of warm gray; the sky and sea were beige and timid. In the picture there were four creatures: two women, a pony, and a boy riding it. The women had twin bodies: large hips and heavy breasts. The pony’s rear was round. Everybody’s expression suggested happiness. The four bodies melted in one solid flat shape, the heads translated into four portraits. Like in a marble Pieta, the figures became one, but these characters were not joined by grief but by the comfort of a cliff walk and a mundane history. An inscription at the bottom in blue. Heavier clogs of ink in parts of the lettering.

“I don’t remember the words, I just remember my heart leaping when I read them and then I went back to ponder on how beautifully the blue of a fountain pen sits on silver bromide.

The parts of Paola’s description that I’ve put in italics refer to purely visual properties of the photograph, aspects of the art of this anonymous picture that moved Paola’s heart to leap up when she read the inscription – which itself is part of the picture, as words are, often, parts of pictures – and to feel the “happiness” and “the comfort of a cliff walk” in Ireland taken by “four creatures” some fifty years ago, that is, at least ten years before Paola was born in northern Italy.

“Visual properties:” in other words, not Paola’s opinions. “Four bodies melted in one solid shape” “Heavier clogs of ink in parts of the lettering,” “round,” “no blacks,” etc., are not opinions or judgments, they are observable things in the picture, physical properties of a physical object. Unless the photograph has faded or been destroyed, they are today exactly as they were when Paola saw the picture. They are forms, and the forms of a picture do not change from viewing to viewing or viewer to viewer.

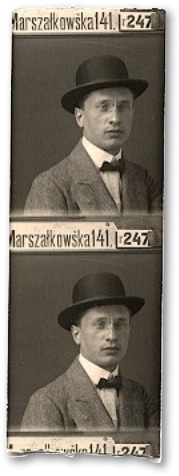

|

Here is one from my personal collection. I found it at a 1970 California swap meet, in a shoe box containing about 200 pictures of a Russian Jewish family—this man, his two brothers, their wives, children and, eventually, grandchildren—taken and saved on their journey beginning in Moscow in the 1910s and ending somewhere in California in the 1930s.

Like the poetry of the photograph Paola described, the poetry of this one derives in part from what has happened to the photograph over time, including the fact that not all a strip of – how many pictures – has been cut into individual frames, so that this picture and its almost double, this man and his almost double, remain in the mysterious human, and beautiful formal relationship that we see here. Paola’s description of her photograph can serve as a guide to the poetry of this one.

|

|

Ben Lifson also conducts private photography tutorials with photographers on three continents.

For information please visit his website, www.benlifson.com |

|